This is the oldest Single Judge Bench criminal appeal of this Court. It was presented on 22.04.1988, admitted on 27.04.1988 and the appellant was directed to be released on bail and realization of fine amount was stayed. After its admission, the case was listed before different Benches on different occasions for hearing but it was adjourned either on the prayer of the learned counsel for the appellant or learned counsel for the Vigilance Department. The matter was listed before me for hearing on 06.08.2020 and I took up the matter through Video Conferencing. The report of the Superintendent of Police, Vigilance Cell, Cuttack revealed that it was intimated to the appellant that the matter would be taken up on 06.08.2020. In spite of that, none appeared on behalf of the appellant. Since the appeal was pending before this Court for more than thirty years, in presence of the learned Senior Standing Counsel for the Vigilance Department, Mr. Deba Prasad Das, Advocate who is having extensive practice on criminal law for more than thirty five years, both in the trial Court as well as before this Court was appointed as Amicus Curiae to conduct the case for the appellant and the Registry was directed to supply the paper book to Mr. Das by 07.08.2020 and to intimate him that the matter would be taken up for hearing in the week commencing from 10.08.2020. Accordingly, Registry supplied the paper book to Mr. Das. On 13.08.2020 when the matter was again listed for hearing and it was taken up through video conferencing, Mr. Das, learned Amicus Curiae was ready for hearing but the learned counsel for the appellant who had filed the criminal appeal in the year 1988 appeared and sought for two weeks adjournment which was refused and accordingly, the hearing was taken up and concluded on that date itself and the judgment was reserved. Mr. Das, learned Amicus Curiae took time till 17.08.2020 to file his written note of submission and accordingly he also filed the same.

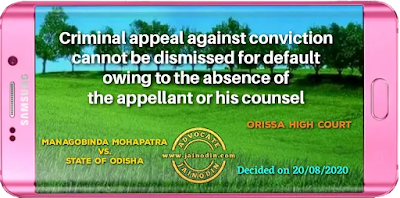

In the case of Bani Singh and others -Vrs.- State of Uttar Pradesh reported in 1996 (II) Orissa Law Reviews (SC) 216, a three Judge Bench of the Hon'ble Supreme Court was called upto to decide the question as to whether the High Court can dismiss an appeal filed by the accused-appellant against the order of conviction and sentence issued by the trial Court, for non-prosecution. Considering the provisions under sections 385 and 386 of Cr.P.C., it was held that the law does not envisage the dismissal of appeal for default or non-prosecution but only contemplates disposal on merits after perusal of the record. It was further held that the law does not enjoin that the Court shall adjourn the case if both the appellant and his lawyer are absent. If the Court does so as a matter of prudence or indulgence, it is a different matter, but it is not bound to adjourn the matter. It can dispose of the appeal after perusing the record and the judgment of the trial Court. If the accused is in jail and cannot, on his own, come to Court, it would be advisable to adjourn the case and fix another date to facilitate the appearance of the accused/appellant if his lawyer is not present. If the lawyer is absent, and the Court deems it appropriate to appoint a lawyer at State expense to assist it, there is nothing in the law to preclude it from doing so. The ratio laid down in the case of Bani Singh (supra) was followed in the case of K.S. Panduranga -Vrs.- State of Karnataka reported in (2013)3 Supreme Court Cases 721 wherein it was held that the High Court cannot dismiss an appeal for non-prosecution simplicitor without examining the merits and the Court is not bound to adjourn the matter if both the appellant or his counsel/lawyer are absent. The Court may, as a matter of prudence or indulgence, adjourn the matter but it is not bound to do so. It can dispose of the appeal after perusing the record and judgment of the trial Court. If the accused is in jail and cannot, on his own, come to Court, it would be advisable to adjourn the case and fix another date to facilitate the appearance of the appellant-accused if his lawyer is not present, and if the lawyer is absent and the Court deems it appropriate to appoint a lawyer at the State expense to assist it, nothing in law would preclude the Court from doing so.

In the case of Shridhar Namdeo Lawand-Vrs.-State of Maharastra reported in 2013 (10) SCALE 52, a three Judge Bench of the Hon'ble Supreme Court held that it is the settled law that Court should not decide criminal case in the absence of the counsel for the accused, as an accused in a criminal case should not suffer for the fault of his counsel and the Court should, in such a situation must appoint another counsel as an amicus curiae to defend the accused.

In the case of Christopher Raj -Vrs.- K.Vijayakumar reported in (2019)7 Supreme Court Cases 398, it was held that when the accused did not enter appearance in the High Court, the High Court should have issued second notice to the appellant-accused or the High Court Legal Services Committee to appoint an Advocate or the High Court could have taken the assistance of Amicus Curiae. When the accused was not represented, without appointing any counsel as Amicus Curiae to defend the accused, the High Court ought not to have decided the criminal appeal on merits.