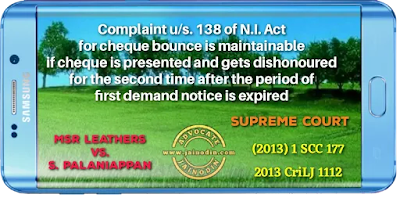

The expression ‘cause of action’ appearing in Section 142 (b) of the Act cannot therefore be understood to be limited to any given requirement out of the three requirements that are mandatory for launching a prosecution on the basis of a dishonoured cheque. Having said that<, every time a cheque is presented in the manner and within the time stipulated under the proviso to Section 138 followed by a notice within the meaning of clause (b) of proviso to Section 138 and the drawer fails to make the payment of the amount within the stipulated period of fifteen days after the date of receipt of such notice, a cause of action accrues to the holder of the cheque to institute proceedings for prosecution of the drawer.[Para No.20]

There is, in our view, nothing either in Section 138 or Section 142 to curtail the said right of the payee, leave alone a forfeiture of the said right for no better reason than the failure of the holder of the cheque to institute prosecution against the drawer when the cause of action to do so had first arisen. Simply because the prosecution for an offence under Section 138 must on the language of Section 142 be instituted within one month from the date of the failure of the drawer to make the payment does not in our view militate against the accrual of multiple causes of action to the holder of the cheque upon failure of the drawer to make the payment of the cheque amount. In the absence of any juristic principle on which such failure to prosecute on the basis of the first default in payment should result in forfeiture, we find it difficult to hold that the payee would lose his right to institute such proceedings on a subsequent default that satisfies all the three requirements of Section 138.[Para No.21]

That brings us to the question whether an offence punishable under Section 138 can be committed only once as held by this Court in Sadanandan Bhadran’s case (supra). The holder of a cheque as seen earlier can present it before a bank any number of times within the period of six months or during the period of its validity, whichever is earlier. This right of the holder to present the cheque for encashment carries with it a corresponding obligation on the part of the drawer to ensure that the cheque drawn by him is honoured by the bank who stands in the capacity of an agent of the drawer vis-à-vis the holder of the cheque. If the holder of the cheque has a right, as indeed is in the unanimous opinion expressed in the decisions on the subject, there is no reason why the corresponding obligation of the drawer should also not continue every time the cheque is presented for encashment if it satisfies the requirements stipulated in that clause (a) to the proviso to Section 138.

There is nothing in that proviso to even remotely suggest that clause (a) would have no application to a cheque presented for the second time if the same has already been dishonoured once. Indeed if the legislative intent was to restrict prosecution only to cases arising out of the first dishonour of a cheque nothing prevented it from stipulating so in clause (a) itself.

In the absence of any such provision a dishonour whether based on a second or any successive presentation of a cheque for encashment would be a dishonour within the meaning of Section 138 and clause (a) to proviso thereof. We have, therefore, no manner of doubt that so long as the cheque remains unpaid it is the continuing obligation of the drawer to make good the same by either arranging the funds in the account on which the cheque is drawn or liquidating the liability otherwise. It is true that a dishonour of the cheque can be made a basis for prosecution of the offender but once, but that is far from saying that the holder of the cheque does not have the discretion to choose out of several such defaults, one default, on which to launch such a prosecution.

The omission or the failure of the holder to institute prosecution does not, therefore, give any immunity to the drawer so long as the cheque is dishonoured within its validity period and the conditions precedent for prosecution in terms of the proviso to Section 138 are satisfied.[Para No.22]