A question of seminal importance has arisen in this case. The query raised relates to the victim compensation scheme under Section 357A(4) of Cr.P.C. and its applicability. Is the provision retrospective or prospective in its application? To paraphrase the query: Would the victim, of a crime that occurred prior to 31.12.2009, be entitled to claim compensation under Section 357A(4) of the Cr. P.C.[Para No.1]

The facts, though not relevant to be narrated in detail, is in a nutshell as follows:

Respondents 2 to 4 are the legal heirs of one late Sri.Sivadas. In a motor vehicle accident that took place on 26-03-2008, Sri. Sivadas succumbed to his injuries. Though a crime was registered by the Alappuzha Traffic Police, the accused could not be identified or traced and the trial has not taken place. In 2013, the legal heirs of late Sivadas applied to the District Legal Services Authority, Alappuzha, seeking compensation from the State under Section 357A(4) of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (for brevity 'the Cr.P.C').[Para No.2]

Pursuant to the application, an enquiry, as contemplated under Section 357A(5) Cr.P.C, was conducted through the Additional District Judge, Alappuzha, who was appointed as the Enquiry Officer. The enquiry report was submitted on 12-09-2013. The report revealed that the applicants are the legal heirs of late Sivadas and that at the time of death he was aged 52 years and a casual labourer. It further stated that considering the circumstances, an amount of Rs.3,03,000/- (Rupees Three lakhs three thousand only) was sufficient compensation that could be awarded to the dependents of late Sri.Sivadas. On the above basis, the 1st respondent by Ext.P1 order, directed the State of Kerala to pay an amount of Rs.3,03,000/- to the dependents of late Sivadas under Section 357A(5) of the Cr.P.C. Ext.P1 is under challenge.[Para No.3]

..............

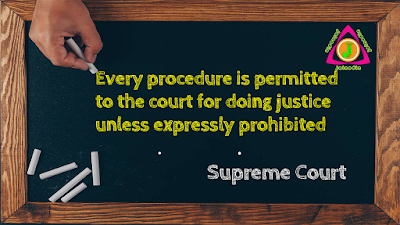

As a substantive law, the aforesaid statutory provision will have only prospective application. However, in the case of Section 357A(1)(4)&(5) Cr.P.C., there is a difference. Rehabilitation of the victim is the scope, purport and import of Section 357A(4) Cr.P.C., when read along with Section 357A (1) Cr.P.C. This is more explicit when understood in the background of the recommendation of the 154th report of the Law Commission of India. Rehabilitation of the victim was a remedial measure. It remedied the weakness in the then existing provisions for compensating the crime victims, especially to those victims, whose perpetrators had not been traced. The provision is remedial. Remedial statutes or provisions are also known as welfare, beneficent or social justice oriented legislation.[Para No.27]

While interpreting a provision brought in as a remedial measure, that too, as a means of welfare for the victims of crimes, in which the perpetrators or offenders have not been identified and in which trial has not taken place, the Court must always be wary and vigilant of not defeating the welfare intended by the legislature. In remedial provisions, as well as in welfare legislation, the words of the statute must be construed in such a manner that it provides the most complete remedy which the phraseology permits. The Court must, always, in such circumstances, interpret the words in such a manner, that the relief contemplated by the provision, is secured and not denied to the class intended to be benefited. [Para No.28]

While interpreting Section 357A(4) Cr.P.C., this Court cannot be oblivious of the agony stricken face of the victim and the trauma and travails such victims have undergone, especially when their offenders have not even been identified or traced out or a trial conducted. The agonizing face of the victims looms large upon this Court while considering the question raised for decision.[Para No.29]

With the aforesaid principles hovering over Section 357A(4)&(5) Cr.P.C., the provision ought to be interpreted in such a manner that it benefits victims. If the said benefit could be conferred without violating the principles of law, then courts must adopt that approach. A substantive law that is remedial, can reckon a past event for applying the law prospectively. Such an approach does not make the substantive law retrospective in its operation. On the other hand, it only caters to the intention of the legislature.[Para No.30]

In other words, when an application is made by a victim of a crime that occurred prior to the coming into force of Section 357A(4) Cr.P.C.,a prospective benefit is given, taking into reckoning an antecedent fact. Adopting such an interpretation does not make the statute or the provision retrospective in operation. It only confers prospective benefits, in certain cases, to even antecedent facts. The statute will remain prospective in application but will draw life from a past event also. The rule against retrospectivity of substantive law is not violated or affected, merely because part of the requisites for action under the provision is drawn from a time antecedent to its passing. Merely because a prospective benefit under a remedial statutory provision is measured by or dependent on antecedent facts, it does not necessarily make the provision retrospective in operation.[Para No.31]