Upon the closer examination of the language used in Section 436-A of the Code, it can be seen without any difficulty or doubt that the benefit intended to be given is for a person who has, during the period of investigation, inquiry or trial under the Code of an offence, not being an offence for which capital punishment has been prescribed as one of the punishments, undergone detention for a period extending up to one half of the maximum period of imprisonment specified for that offence under that law. In such a case, the person is required to be released on his personal bond with or without sureties in normal course of circumstances. But, there could be some special circumstances justifying his further detention, for reasons to be recorded, which makes the right of the person limited and not absolute. This is evident from the first proviso which lays down that the Court may, after hearing the Public Prosecutor and for reasons to be recorded in writing, order continued detention of the person for a period longer than one half of the period mentioned in the Section or release him on bail instead of the personal bond with or without sureties. However, this limited right has the potential of becoming absolute when the condition prescribed in second proviso is fulfilled. The condition is that if the person has been detained during the period of investigation, inquiry or trial for more than maximum period of imprisonment provided for an offence under that law, the person has to be released. There is also an explanation appended to the section. It lays down that in computing the period of detention for granting bail, the period of detention passed due to delay in proceeding caused by the accused shall be excluded.[Para No.18]

Reading the Section as a whole, we find that the benefit under the section has been intended to be given only to the under-trial prisoners. The words "during the period of investigation, inquiry or trial" and the words "maximum period of imprisonment specified for that offence" are significant. They indicate that only that person who has undergone detention for a period of one half or more of the maximum prescribed punishment during investigation, inquiry or trial under the Code who is eligible for his release on personal bond with or without sureties or bail, as the case may be. The Section does not say that a person who has been detained for one half period of imprisonment imposed would be eligible. Mentioning of "the maximum period of imprisonment specified for that offence under that law" and omission of the words "punishment imposed" shows that the legislature was aware of the difference in the status of an undertrial prisoner and a convict, and with it of the consequences of detaining a person who enjoys presumption of innocence till found guilty for unduly long time. Such presumption of innocence being absent in case of a convict, the legislature refrained, and consciously, from mentioning the words "punishment imposed". This clearly shows the intention of the legislature to confer the benefit on the under- trials and not the convicts. This being the position, we do not think that rule of liberal construction would have any application here.[Para No.19]

As these provisions create a step-wise mechanism to procedurally deal with crimes and so the word, "trial" used in Section 436-A would get it's meaning in the context of this scheme of the Code, at least for the purpose which is sought to be achieved by the provision of Section 436-A. Under this scheme of the Code, "trial" of a person accused of an offence is contemplated only by a Court having original criminal jurisdiction or assuming original criminal jurisdiction after committal of a Sessions case and appeal as a remedy against the judgment of conviction and/or sentence or even acquittal has been made available before the Court exercising Appellate jurisdiction. In this sense, so far as the Section 436- A benefit is concerned, the word "trial" has to be understood in contra-distinction to an "appeal proceeding". Our conclusion is further bolstered up by the provisions contained in Section 353. Provisions contained in Section 389 also help us in drawing of such an inference. It would be, therefore, convenient for us to quote relevant portions of these sections here. They are as under :

"353. Judgment - (1) The judgment in every trial in any Criminal Court of original jurisdiction shall be pronounced in open Court by the presiding officer immediately after the termination of the trial or at some subsequent time of which notice shall be given to the parties or their pleaders,

(a) by delivering the whole of the judgment; or

(b) by reading out the whole of the judgment; or

(c) by reading out the operative part of thej udgment and explaining the substance of the judgment in a language which is understood by the accused or his pleader."

"389. Suspension of sentence pending the appeal; release of appellant on bail. - (1) Pending any appeal by a convicted person, the Appellate Court may, for reasons to be recorded by it in writing, order that the execution of the sentence or order appealed against be suspended and, also, if he is in confinement, that he be released on bail, or on his own bond:

Provided that the Appellate Court shall, before releasing on bail or on his own bond a convicted person who is convicted of an offence punishable with death or imprisonment for life or imprisonment for a term of not less than ten years, shall give opportunity to the Public Prosecutor for showing cause in writing against such release:"

It is clear from Section 353 that it requires a criminal Court to pronounce judgment in every trial in open Court immediately "after the termination of the trial or at some subsequent time". It is indicative of the fact that upon pronouncement of the judgment, in the contemplation of the scheme of the Code, there occurs termination of the trial. If we examine Section 389 of the Code, on the backdrop of Section 353, we would find that under the scheme of the Code, appeal has been considered to be a stage separate from trial, which comes into being after pronouncement of the judgment upon termination of the trial. In other words, unless there is termination of trial, there is no question of stage of appeal being born. That means the words "trial" and "appeal" have been used in distinctive sense thereby signaling that no one makes a mistake in understanding that "trial" is not synonymous with "appeal", when it comes to extending benefit available to an under trial prisoner to a convict undergoing sentence of imprisonment.

Of course, in general sense, appeal could be said to be an extension of trial on the parameters of rights available to a convict, principles to be followed by Appellate Court in appreciation of evidence and power of Appellate Court. But, this is not so for the purposes of Section 436-A of the Code. This is the reason why in Section 389 of the Code, the words "trial of the person", "are not used and instead the words, "pending any appeal by a convicted person" are employed for considering suspension of sentence of the convict and grant of bail to him.[Para No.23]

The discussion thus far made would show that even though an appeal could be said to be continuation of trial in the general sense of the term, it is not so for the purposes of Section 436-A of the Code. The word "trial" used in Section 436-A of the Code is for achieving a certain purpose, a defined goal of reducing the woes of a person in jail as he faces trial, even before he is found guilty and to a larger extent also to decongest overcrowded jails. The provision is benefic and remedial and, therefore, it must be understood in the sense which sub-serves the purpose, which remedies the situation or otherwise the remedial medicine may itself become the malady. So, the meaning plainly conveyed by Section 436-A is that its benefit is intended only for under-trial prisoners, and it is not possible to make any different or alternate construction. When two different constructions are not fairly possible, contingency of adopting that construction which favours the convict by granting him benefit of Section 436-A of the Code does not arise and so, rule of liberal construction would have no application here.[Para No.25]

Here is a case where the intention of the Parliament to confer the benefit of Section 436-A of the Code upon only undertrial prisoners is clearly found in the words used in Section 436-A of the Code and understood in the context of the scheme of the Code. In the case of State of Himachal Pradesh and anr. Vs. Kailash Chand Mahajan and ors., AIR 1992 SC 1277, p. 1300, the Hon'ble Apex Court has held that the legislative intention behind an enactment and the true meaning thereof is derived by considering the meaning of the words used in the enactment in the light of it's discernible purpose or object which comprehends the mischief and provides a remedy. This formulation later came to be known as the "cardinal principle of construction" (See Union of India Vs. Elphinstone Spinning and Weaving Co. Ltd., AIR 2001 SC 724, p. 740).[Para No.26]

There are more indications appearing from the section. One of them is the placement in the Code of the Section, which points out that the benefit has been intended by the Parliament to be only for the under-trial prisoners and not convicts. Essential prescription of the Section is that one half period of detention has to be counted not in relation to the punishment awarded but in relation to the maximum period of imprisonment prescribed for an offence. If it were the intention of the legislature to confer this benefit even upon a convict, it would also have made suitable provision by making appropriate reference to the sentence imposed. But, that is not the case here. As against this, Section 389 of the Code specifically refers to a convicted person and the power of the Court to suspend the sentence or order appealed against and also direct release of the convict on bail, if he is in confinement. Section 389 of the Code has not been amended so as to include the limited right given by Section 436-A to a person under investigation or inquiry or facing trial. The other indicator is that Section 436-A has been inserted in Chapter- XXXIII containing provisions as to bail and bonds. The provisions contained in this Chapter, deal with bail and bonds and the principles applicable to them in relation to a person accused of or suspected of commission of an offence. These provisions do not by themselves enable a convict to secure bail, and he has to take recourse to Section 389 of the Code, which makes possibility of getting bail for a convict a reality, subject to appellate court suspending his sentence. In other words the provision does not make the event of grant of bail as independent of the satisfaction of the Court as regards the need for suspending the sentence or order appealled against, till final disposal of the appeal and it is only upon recording necessary satisfaction that a convict would succeed in getting bail. So, in a pending appeal there is no right of bail for a convict which is alive and available for him to be taken advantage of at any point of time desired by him. The right remains eclipsed by the requirement of suspension of sentence and becomes clearly visible when the eclipse is removed. Even after the right becomes available, it's realization depends on the discretion of the Court. But that is a different matter. The point here is of the exercise of right being dependent on suspension of sentence by the Court. That would show that the right of bail in Section 389 of the Code is consequential to suspension of the sentence and unless the first requirement is fulfilled, the consequence of bail of convict would not happen. If the legislature had intended that the benefit under Section 436-A of the Code should be given even to a convict before an Appellate Court, it would have amended suitably Section 389 of the Code. The legislature did not do it. It would show that the legislative policy was limited to extending benefit only to an undertrial prisoner and not to convicts whose appeal is pending before the Appellate Court under Section 374 of the Code.[Para No.28]

It would be clear from above that Supreme Court did not reject the submission that Section 436-A of the Code was not applicable to an appeal proceeding, rather, it added that as a supplement to Section 436-A of the Code and consistent with its spirit, an under-trial prisoner completing period of custody which is in excess of the sentence likely to be awarded, if conviction was to be recorded, must be released on personal bond. The Apex Court having thus considered the issue of applicability of Section 436-A of the Code and having extended further its benefit only to under- trial prisoners and not to convicts, cannot be said to have approved, even by implication, the proposition that the benefit is applicable to a convict. In fact, a conclusion in reversal would arise that Supreme Court did not reject the submission that benefit under Section 436-A was available only during trial, thereby impliedly refusing to apply it to an appeal proceeding. On realising the ratio of Hussain (supra), learned counsel for the applicant has fairly submitted that he would not say anything more in reply. It is now clear that decisions in Pradip (supra) and Mudassir Hussain (supra), really do not present correct legal position, though in Pradip (supra), we must say, the Division Bench has not categorically held that the provision of Section 436-A of the Code is applicable to an appeal proceeding. It was only observed that in view of provisions of Section 436-A of the Code coupled with the fact that as the Bench was not in a position to take up the appeal immediately for final hearing in near future, the Bench would grant bail. This is suggestive of the fact that the Division Bench appears to have drawn inspiration from the principles stated in Section 436-A of the Code and chose to apply them together with other relevant circumstances so as to effectuate the right of a convict regarding expeditious disposal of a criminal appeal. Following the consistent view taken by the Apex Court since the case Hussainara (supra) till date, we are inclined to say that the principles stated in Section 436-A of the Code can be used by an appellate court while considering application of a convict filed under Section 389 of the Code seeking suspension of sentence and bail, as constituting one of the relevant criteria for exercise of its discretion and of course not as a matter of any right or course.[Para No.30]

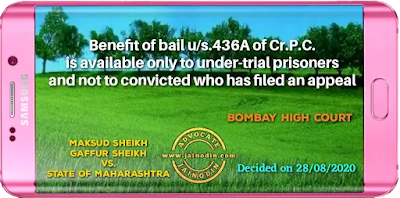

With this discussion, the inevitability of our conclusion is writ large and it provides a negative answer to the question referred to us. To be specific, we answer the question in terms that a convict who has challenged his conviction under Section 374 of the Code, is not entitled to the benefit of Section 436-A of the Code. [Para No.34]

Bombay High Court

Maksud Sheikh Gaffur Sheikh

Vs.

State Of Maharashtra

Decided on 28/08/2020