The expression ‘cause of action’ appearing in Section 142 (b) of the Act cannot therefore be understood to be limited to any given requirement out of the three requirements that are mandatory for launching a prosecution on the basis of a dishonoured cheque. Having said that<, every time a cheque is presented in the manner and within the time stipulated under the proviso to Section 138 followed by a notice within the meaning of clause (b) of proviso to Section 138 and the drawer fails to make the payment of the amount within the stipulated period of fifteen days after the date of receipt of such notice, a cause of action accrues to the holder of the cheque to institute proceedings for prosecution of the drawer. [Para No.20]

There is, in our view, nothing either in Section 138 or Section 142 to curtail the said right of the payee, leave alone a forfeiture of the said right for no better reason than the failure of the holder of the cheque to institute prosecution against the drawer when the cause of action to do so had first arisen. Simply because the prosecution for an offence under Section 138 must on the language of Section 142 be instituted within one month from the date of the failure of the drawer to make the payment does not in our view militate against the accrual of multiple causes of action to the holder of the cheque upon failure of the drawer to make the payment of the cheque amount. In the absence of any juristic principle on which such failure to prosecute on the basis of the first default in payment should result in forfeiture, we find it difficult to hold that the payee would lose his right to institute such proceedings on a subsequent default that satisfies all the three requirements of Section 138. [Para No.21]

Coming then to the question whether there is anything in Section 142(b) to suggest that prosecution based on subsequent or successive dishonour is impermissible, we need only mention that the limitation which Sadanandan Bhadran’s case (supra) reads into that provision does not appear to us to arise. We say so because while a complaint based on a default and notice to pay must be filed within a period of one month from the date the cause of action accrues, which implies the date on which the period of 15 days granted to the drawer to arrange the payment expires, there is nothing in Section 142 to suggest that expiry of any such limitation would absolve him of his criminal liability should the cheque continue to get dishonoured by the bank on subsequent presentations.

Applying the above rule of interpretation and the provisions of Section 138, we have no hesitation in holding that

The controversy, in our opinion, can be seen from another angle also. If the decision in Sadanandan Bhadran’s case (supra) is correct, there is no option for the holder to defer institution of judicial proceedings even when he may like to do so for so simple and innocuous a reason as to extend certain accommodation to the drawer to arrange the payment of the amount. Apart from the fact that an interpretation which curtails the right of the parties to negotiate a possible settlement without prejudice to the right of holder to institute proceedings within the outer period of limitation stipulated by law should be avoided we see no reason why parties should, by a process of interpretation, be forced to launch complaints where they can or may like to defer such action for good and valid reasons. After all, neither the courts nor the parties stand to gain by institution of proceedings which may become unnecessary if cheque amount is paid by the drawer. The magistracy in this country is over-burdened by an avalanche of cases under Section 138 of Negotiable Instruments Act. If the first default itself must in terms of the decision in Sadanandan Bhadran’s case (supra) result in filing of prosecution, avoidable litigation would become an inevitable bane of the legislation that was intended only to bring solemnity to cheques without forcing parties to resort to proceedings in the courts of law. While there is no empirical data to suggest that the problems of overburdened magistracy and judicial system at the district level is entirely because of the compulsions arising out of the decisions in Sadanandan Bhadran’s case (supra), it is difficult to say that the law declared in that decision has not added to court congestion.[Para No.33]

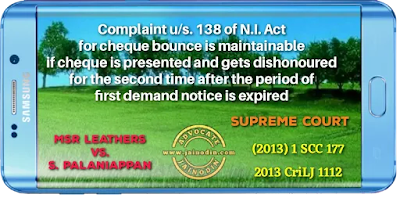

In the result, we overrule the decision in Sadanandan Bhadran’s case (supra) and hold that prosecution based upon second or successive dishonour of the cheque is also permissible so long as the same satisfies the requirements stipulated in the proviso to Section 138 of the Negotiable Instruments Act. The reference is answered accordingly. The appeals shall now be listed before the regular Bench for hearing and disposal in light of the observations made above.[Para No.34]

Supreme Court of India

MSR Leathers

Vs.

S. Palaniappan

(2013) 1 SCC 17

2013 CriLJ 1112