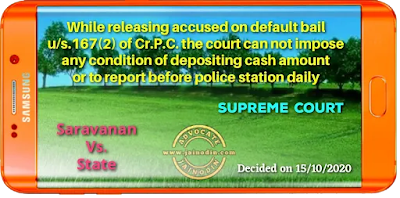

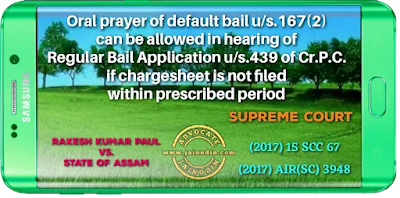

Having heard the learned counsel for the respective parties and considering the scheme and the object and purpose of default bail/statutory bail, we are of the opinion that the High Court has committed a grave error in imposing condition that the appellant shall deposit a sum of Rs.8,00,000/ while releasing the appellant on default bail/statutory bail. It appears that the High Court has imposed such a condition taking into consideration the fact that earlier at the time of hearing of the regular bail application, before the learned Magistrate, the wife of the appellant filed an affidavit agreeing to deposit Rs.7,00,000/. However, as observed by this Court in catena of decisions and more particularly in the case of Rakesh Kumar Paul (supra), where the investigation is not completed within 60 days or 90 days, as the case may be, and no chargesheet is filed by 60 th or 90th day, accused gets an “indefeasible right” to default bail, and the accused becomes entitled to default bail once the accused applies for default bail and furnish bail. Therefore, the only requirement for getting the default bail/statutory bail under Section 167(2), Cr.P.C. is that the accused is in jail for more than 60 or 90 days, as the case may be, and within 60 or 90 days, as the case may be, the investigation is not completed and no

chargesheet is filed by 60th or 90th day and the accused applies for default bail and is prepared to furnish bail. No other condition of deposit of the alleged amount involved can be imposed. Imposing such condition while releasing the accused on default bail/statutory bail would frustrate the very object and purpose of default bail under Section 167(2), Cr.P.C. As observed by this Court in the case of Rakesh Kumar Paul (supra) and in other decisions, the accused is entitled to default bail/statutory bail, subject to the eventuality occurring in Section 167, Cr.P.C., namely, investigation is not completed within 60 days or 90 days, as the case may be, and no chargesheet is filed by 60 th or 90th day and the accused applies for default bail and is prepared to furnish bail.[Para No.9]

As observed hereinabove and even from the impugned orders passed by the High Court, it appears that the High Court while releasing the appellant on default bail/statutory bail has imposed the condition to deposit Rs.8,00,000/ taking into consideration that earlier before the learned Magistrate and while considering the regular bail application under Section 437 Cr.P.C., the wife of the accused filed an affidavit to deposit Rs.7,00,000/. That cannot be a ground to impose the condition

to deposit the amount involved, while granting default bail/statutory bail.[Para No.9.1]