06 April 2021

It is appropriate case for grant of anticipatory bail when F.I.R. is lodged by way of counterblast to an earlier F.I.R lodged/complaint filed by the accused against the informant in near proximity of time

27 December 2020

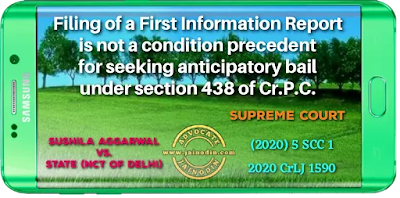

filing of a first information report is not a condition precedent to the exercise of the power under Section 438 of Cr.P.C.

(i) Grant of an order of unconditional anticipatory bail would be “plainly contrary to the very terms of Section 438.” Even though the terms of Section 438(1) confer discretion, Section 438(2) “confers on the court the power to include such conditions in the direction as it may think fit in the light of the facts of the particular case, including the conditions mentioned in clauses (i) to (iv) of that sub-section.”

(ii) Grant of an order under Section 438(1) does not per se hamper investigation of an offence; Section 438(1)(i) and (ii) enjoin that an accused/applicant should co-operate with investigation. Sibbia (supra) also stated that courts can fashion appropriate conditions governing bail, as well. One condition can be that if the police make out a case of likely recovery of objects or discovery of facts under Section 27 (of the Evidence Act, 1872), the accused may be taken into custody. Given that there is no formal method prescribed by Section 46 of the Code if recovery is made during a statement (to the police) and pursuant to the accused volunteering the fact, it would be a case of recovery during “deemed arrest” (Para 19 of Sibbia).

(iii)

(iv) While the power of granting anticipatory bail is not ordinary, at the same time, its use is not confined to exceptional cases (Para 22, Sibbia).

(v) It is not justified to require courts to only grant anticipatory bail in special cases made out by accused, since the power is extraordinary, or that several considerations – spelt out in Section 437- or other considerations, are to be kept in mind. (Para 24-25, Sibbia).

(vi) Overgenerous introduction (or reading into) of constraints on the power to grant anticipatory bail would render it Constitutionally vulnerable. Since fair procedure is part of Article 21, the court should not throw the provision (i.e. Section 438) open to challenge “by reading words in it which are not to be found therein.” (Para 26).

(vii) There is no “inexorable rule” that anticipatory bail cannot be granted unless the applicant is the target of mala fides. There are several relevant considerations to be factored in, by the court, while considering whether to grant or refuse anticipatory bail. Nature and seriousness of the proposed charges, the context of the events likely to lead to the making of the charges, a reasonable possibility of the accused’s presence not being secured during trial; a reasonable apprehension that the witnesses might be tampered with, and “the larger interests of the public or the state” are some of the considerations.

(viii) There can be no presumption that any class of accused- i.e. those accused of particular crimes, or those belonging to the poorer sections, are likely to abscond. (Para 32, Sibbia).

(ix) Courts should exercise their discretion while considering applications for anticipatory bail (as they do in the case of bail). It would be unwise to divest or limit their discretion by prescribing “inflexible rules of general application.”. (Para 33, Sibbia).

(x) The apprehension of an applicant, who seeks anticipatory bail (about his imminent or possible arrest) should be based on reasonable grounds, and rooted on objective facts or materials, capable of examination and evaluation, by the court, and not based on vague un-spelt apprehensions. (Para 35, Sibbia).

(xi)

(xii)

(xiii) Anticipatory bail can be granted even after filing of an FIR- as long as the applicant is not arrested. However, after arrest, an application for anticipatory bail is not maintainable. (Para 38-39, Sibbia).

27 October 2020

Bail can not be denied to chargesheeted accused on the ground of abscondence of other accused

17 October 2020

Bail should be granted or refused based on the probability of attendance of the party to take his trial

By now it is well settled that

gravity alone cannot be a decisive ground to deny bail, rather competing factors are required to be balanced by the court while exercising its discretion. It has been repeatedly held by the Hon'ble Apex Court thatobject of bail is to secure the appearance of the accused person at his trial by reasonable amount of bail. The object of bail is neither punitive nor preventative. The Hon'ble Apex Court in Sanjay Chandra versus Central Bureau of Investigation (2012)1 Supreme Court Cases 49; has been held as under: "The object of bail is to secure the appearance of the accused person at his trial by reasonable amount of bail.The object of bail is neither punitive nor preventative. Deprivation of liberty must be considered a punishment, unless it can be required to ensure that an accused person will stand his trial when called upon.The Courts owe more than verbal respect to the principle that punishment begins after conviction, and that every man is deemed to be innocent until duly tried and duly found guilty. Detention in custody pending completion of trial could be a cause of great hardship. From time to time, necessity demands that some unconvicted persons should be held in custody pending trial to secure their attendance at the trial but in such cases, "necessity" is the operative test. In India , it would be quite contrary to the concept of personal liberty enshrined in the Constitution that any person should be punished in respect of any matter, upon which, he has not been convicted or that in any circumstances, he should be deprived of his liberty upon only the belief that he will tamper with the witnesses if left at liberty, save in the most extraordinary circumstances. Apart from the question of prevention being the object of refusal of bail,one must not lose sight of the fact that any imprisonment before conviction has a substantial punitive content and it would be improper for any court to refuse bail as a mark of disapproval of former conduct whether the accused has been convicted for it or not or to refuse bail to an unconvicted person for the propose of giving him a taste of imprisonment as a lesson." [Para No.5]

Needless to say

29 September 2020

Accused can be released on interim bail on the ground of snail speed of the trial

Successive application for bail is permissible under substantial change of circumstances which has direct impact on the earlier decision and not merely cosmetic changes

"19.....However, unintentional and unavoidable delays or administrative factors over which prosecution has no control, such as, over- crowded court dockets, absence of the presiding officers, strike by the lawyers, delay by the superior forum in notifying the designated Judge, (in the present case only), the matter pending before the other forums, including High Courts and Supreme Courts and adjournment of the criminal trial at the instance of the accused, may be a good cause for the failure to complete the trial within a reasonable time. This is only illustrative and not exhaustive. Such delay or delays cannot be violative of accused's right to a speedy trial and needs to be excluded while deciding whether there is unreasonable and unexplained delay..."

25 September 2020

While deciding bail application, it cannot be presumed that petitioner will flee justice or will influence the investigation/witnesses

Grant of bail cannot be thwarted merely by asserting that offence is grave.

Consequences of pre-trial detention are grave.

In AIR 2019 SC 5272, titled P. Chidambaram v. Central Bureau of Investigation, CBI had opposed the bail plea on the grounds of:- (i) flight risk; (ii) tampering with evidence; and (iii) influencing witnesses. The first two contentions were rejected by the High Court. But bail was declined on the ground that possibility of influencing the witnesses in the ongoing investigation cannot be ruled out. Hon'ble Apex Court after considering (2001) 4 SCC 280, titled Prahlad Singh Bhati v. NCT, Delhi and another;( 2004) 7 SCC 528, titled Kalyan Chandra sarkar v.R ajesh Ranjan and another; (2005) 2 SCC 13, titled Jayendra Saraswathi Swamigal v. State of Tamil Nadu and (2005) 8 SCC 21, titled State of U.P. through CBI v.Amarmani Tripathi, observed as under:-

"26. As discussed earlier, insofar as the "flight risk" and "tampering with evidence" are concerned, the High Court held in favour of the appellant by holding that the appellant is not a "flight risk" i.e. "no possibility of his abscondence". The High Court rightly held that by issuing certain directions like "surrender of passport", "issuance of look out notice", "flight risk" can be secured. So far as "tampering with evidence" is concerned, the High Court rightly held that the documents relating to the case are in the custody of the prosecuting agency, Government of India and the Court and there is no chance of the appellant tampering with evidence.

28. So far as the allegation of possibility of influencing the witnesses, the High Court referred to the arguments of the learned Solicitor General which is said to have been a part of a "sealed cover" that two material witnesses are alleged to have been approached not to disclose any information regarding the appellant and his son and the High Court observed that the possibility of influencing the witnesses by the appellant cannot be ruled out. The relevant portion of the impugned judgment of the High Court in para (72) reads as under:

"72. As argued by learned Solicitor General, (which is part of 'Sealed Cover', two material witnesses (accused) have been approached for not to disclose any information regarding the petitioner and his son (co-accused). This court cannot dispute the fact that petitioner has been a strong Finance Minister and Home Minister and presently, Member of Indian Parliament. He is respectable member of the Bar Association of Supreme Court of India. He has long standing in BAR as a Senior Advocate. He has deep root in the Indian Society and may be some connection in abroad. But, the fact that he will not influence the witnesses directly or indirectly, cannot be ruled out in view of above facts. Moreover, the investigation is at advance stage, therefore, this Court is not inclined to grant bail."

29. FIR was registered by the CBI on 15.05.2017. The appellant was granted interim protection on 31.05.2018 till 20.08.2019. Till the date, there has been no allegation regarding influencing of any witness by the appellant or his men directly or indirectly. In the number of remand applications, there was no whisper that any material witness has been approached not to disclose information about the appellant and his son. It appears that only at the time of opposing the bail and in the counter affidavit filed by the CBI before the High Court, the averments were made that "....the appellant is trying to influence the witnesses and if enlarged on bail, would further pressurize the witnesses....". CBI has no direct evidence against the appellant regarding the allegation of appellant directly or indirectly influencing the witnesses. As rightly contended by the learned Senior counsel for the appellant, no material particulars were produced before the High Court as to when and how those two material witnesses were approached. There are no details as to the form of approach of those two witnesses either SMS, email, letter or telephonic calls and the persons who have approached the material witnesses. Details are also not available as to when, where and how those witnesses were approached.

31. It is to be pointed out that the respondent - CBI has filed remand applications seeking remand of the appellant on various dates viz. 22.08.2019, 26.08.2019, 30.08.2019, 02.09.2019, 05.09.2019 and 19.09.2019 etc. In these applications, there were no allegations that the appellant was trying to influence the witnesses and that any material witnesses (accused) have been approached not to disclose information about the appellant and his son. In the absence of any contemporaneous materials, no weight could be attached to the allegation that the appellant has been influencing the witnesses by approaching the witnesses. The conclusion of the learned Single Judge "...that it cannot be ruled out that the petitioner will not influence the witnesses directly or indirectly....." is not substantiated by any materials and is only a generalised apprehension and appears to be speculative. Mere averments that the appellant approached the witnesses and the assertion that the appellant would further pressurize the witnesses, without any material basis cannot be the reason to deny regular bail to the appellant; more so, when the appellant has been in custody for nearly two months, co-operated with the investigating agency and the charge sheet is also filed.

32. The appellant is not a "flight risk" and in view of the conditions imposed, there is no possibility of his abscondence from the trial. Statement of the prosecution that the appellant has influenced the witnesses and there is likelihood of his further influencing the witnesses cannot be the ground to deny bail to the appellant particularly, when there is no such whisper in the six remand applications filed by the prosecution. The charge sheet has been filed against the appellant and other co-accused on 18.10.2019. The appellant is in custody from 21.08.2019 for about two months. The co-accused were already granted bail. The appellant is said to be aged 74 years and is also said to be suffering from age related health problems. Considering the above factors and the facts and circumstances of the case, we are of the view that the appellant is entitled to be granted bail."[Para No.5.v.6]

16 September 2020

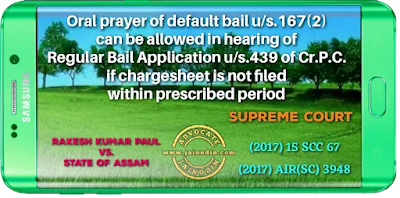

Oral prayer of default bail u/s.167(2) can be allowed in hearing of Regular Bail Application u/s.439 of Cr.P.C. if chargesheet is not filed within prescribed period

30 August 2020

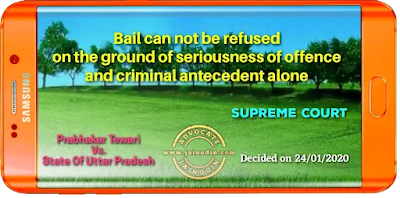

Bail can not be refused on the ground of seriousness of offence and criminal antecedent alone

21 August 2020

In computing period of 60/90 days for default bail u/s.167(2) of CrPC, first day of remand is to be included

18 July 2020

Prison is primarily for punishing convicts ; not for detaining undertrials in order to send any 'message' to society

“.... Granting of bail at this early stage may send an adverse message in the society and such crimes should not

be allowed to happen in the national capital. ....”.

09 July 2020

Bail application u/s.167(2) of CrPC must be dispose of forthwith

"11. The law on the point as to the rights of an accused who is in custody pending investigation and where the investigation is not completed within the period prescribed under Section 167(2) of the Code, is crystallised in the judgment of this Court in Uday Mohanlal Acharya v. State of Maharashtra. This case took into account the decision of this Court in Hitendra Vishnu Thakur v. State of Maharashtra, Sanjay Dutt (2) v. State and Bipin Shantilal Panchal v. State of Gujarat. Pattanaik, J. (as the learned Chief Justice then was) speaking for the majority recorded conclusions in para 13 of his judgment. For the present purposes, we may extract Conclusions 3 and 4 as under: (Uday Mohanlal Acharya case, SCC p. 473, para 13) "13. ... 3. On the expiry of the said period of 90 days or 60 days, as the case may be, an indefeasible right accrues in favour of the accused for being released on bail on account of default by the investigating agency in the completion of the investigation within the period prescribed and the accused is entitled to be released on bail, if he is prepared to and furnishes the bail as directed by the Magistrate.

4. When an application for bail is filed by an accused for enforcement of his indefeasible right alleged to have been accrued in his favour on account of default on the part of the investigating agency in completion of the investigation within the specified period, the Magistrate/court must dispose of it forthwith, on being satisfied that in fact the accused has been in custody for the period of 90 days or 60 days, as specified and no charge-sheet has been filed by the investigating agency. Such prompt action on the part of the Magistrate/court will not enable the prosecution to frustrate the object of the Act and the legislative mandate of an accused being released on bail on account of the default on the part of the investigating agency in completing the investigation within the period stipulated."

13 May 2020

Denial of default bail u/s.167(2) of Cr.P.C. amounts to violation of his fundamental right under Article 21 of the Constitution of India

Article 21 states that no person shall be deprived of his personal liberty except according to procedure established by law. So long as the language of Section 167(2) of Cr.Pc remains as it is, I have to necessarily hold that denial of compulsive bail to the petitioner herein will definitely amount to violation of his fundamental right under Article 21 of the Constitution of India.[Para No.14]