18 October 2020

The proof of demand is an indispensable essentiality to prove the offence under The Prevention of Corruption Act

17 October 2020

Bail should be granted or refused based on the probability of attendance of the party to take his trial

By now it is well settled that

gravity alone cannot be a decisive ground to deny bail, rather competing factors are required to be balanced by the court while exercising its discretion. It has been repeatedly held by the Hon'ble Apex Court thatobject of bail is to secure the appearance of the accused person at his trial by reasonable amount of bail. The object of bail is neither punitive nor preventative. The Hon'ble Apex Court in Sanjay Chandra versus Central Bureau of Investigation (2012)1 Supreme Court Cases 49; has been held as under: "The object of bail is to secure the appearance of the accused person at his trial by reasonable amount of bail.The object of bail is neither punitive nor preventative. Deprivation of liberty must be considered a punishment, unless it can be required to ensure that an accused person will stand his trial when called upon.The Courts owe more than verbal respect to the principle that punishment begins after conviction, and that every man is deemed to be innocent until duly tried and duly found guilty. Detention in custody pending completion of trial could be a cause of great hardship. From time to time, necessity demands that some unconvicted persons should be held in custody pending trial to secure their attendance at the trial but in such cases, "necessity" is the operative test. In India , it would be quite contrary to the concept of personal liberty enshrined in the Constitution that any person should be punished in respect of any matter, upon which, he has not been convicted or that in any circumstances, he should be deprived of his liberty upon only the belief that he will tamper with the witnesses if left at liberty, save in the most extraordinary circumstances. Apart from the question of prevention being the object of refusal of bail,one must not lose sight of the fact that any imprisonment before conviction has a substantial punitive content and it would be improper for any court to refuse bail as a mark of disapproval of former conduct whether the accused has been convicted for it or not or to refuse bail to an unconvicted person for the propose of giving him a taste of imprisonment as a lesson." [Para No.5]

Needless to say

16 October 2020

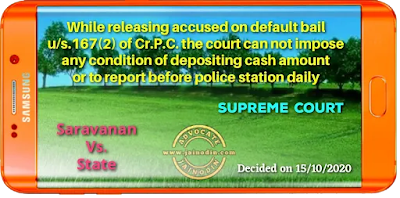

While releasing accused on default bail u/s.167(2) of Cr.P.C. the court can not impose any condition of depositing cash amount or to report before police station daily

15 October 2020

Residence Order passed under The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act does not impose any embargo for filing or continuing civil suit seeking permanent injuction against daughter-in-law

14 October 2020

Mere recovery of blood stained weapon cannot be construed as proof for the murder

For proving the contents of memorandum prepared u/s.27 of Evidence Act, the Investigating Officer must state the exact narration of facts in such document in his own words while deposing before the Court

17. Now as regards the proving of such information, the matter seems to us to be governed by Sections 60, 159 and 160 of the Evidence Act. It is correct thatstatements and reports prepared outside the court cannot by themselves be accepted as primary or substantive evidence of the facts stated therein. Section 60 of the Evidence Act lays down that oral evidence must, in all cases whatever, be direct, that is to say, if it refers to a fact which could be seen, it must be the evidence of a witness who says he saw it, and if it refers to a fact which could be heard, it must be the evidence of a witness who says he heard it and so on. Section 159 then permits a witness while under examination to refresh his memory by referring to any writing made by himself at the time of the transaction concerning which he is questioned, or so soon afterwards that the court considers it likely that the transaction was at that time fresh in the memory. Again, with the permission of the court, the witness may refresh, his memory by referring to a copy of such document. And the witness may even refer to any such writing made by any other person but which was read by him at the time the transaction was fresh in his memory and when he read it, he knew it to be correct. Section 160 then provides for cases where the witness has no independent recollection say, from lapse of memory, of the transaction to which he wants to testify by looking at the document and states that although he has no such recollection he is sure that the contents of the document were correctly recorded at the time they were. It seems to us that where a case of this character arises and the document itself has been tendered in evidence, the document becomes primary evidence in the case. See Jagan Nath v. Emperor, AIR 1932 Lah 7.The fundamental distinction between the two sections is that while under Section 159 it is the witness's memory or recollection which is evidence, the document itself not having been tendered in evidence; under Section 160, it is the document which is evidence of the facts contained in it. It has been further held that in order to bring a case under Section 160, though the witness should ordinarily affirm on oath that he does not recollect the facts mentioned in the document, the mere omission to say so will not make the document inadmissible provided the witness swears that he is sure that the facts are correctly recorded in the document itself. Thus in Partab Singh v. Emperor, AIR 1926 Lah 310 it was held that where the surrounding circumstances intervening between the recording of a statement and the trial would as a matter of normal human experience render it impossible for a police officer to recollect and reproduce the words used, his statement should be treated as if he had prefaced it by stating categorically that he could not remember what the deceased in that case had said to him. Putting the whole thing in somewhat different language, what was held was that Section 160 of the Act applies equally when the witness states in so many words that he has no independent recollection of the precise words used, or when it should stand established beyond doubt that that should be so as a matter of natural and necessary conclusion from the surrounding circumstances.18. Again, in Krishnama v. Emperor, AIR 1931 Mad 430 a Sub-Assistant Surgeon recorded the statement made by the deceased just before his death, which took place in April, 1930, and the former was called upon to give evidence some time in July, 1930. In the Sessions Court he just put in the recorded statement of the deceased which was admitted in evidence. On appeal it was objected that such statement was wrongly admitted inasmuch as the witness did not use it to refresh his memory nor did he attempt from recollection to reproduce the words used by the accused. It was held that he could not have been expected to reproduce the words of the deceased, and therefore, he was entitled to put in the document as a correct record of what the deponent had said at the time on the theory that the statement should be treated as if the witness had prefaced it by stating categorically that he could not remember what the deceased had said.19. Again in Public Prosecutor v. Venkatarama Naidu, AIR 1943 Mad 542, the question arose how the notes of a speech taken by a police officer be admitted in evidence. It was held that it was not necessary that the officer should be made to testify orally after referring to those notes. The police officer should describe his attendance, the making of the relevant speech and give a description of its nature so as to identify his presence there and his attention to what was going on, and that after that it was quite enough it he said "I wrote down that speech and this is what I took down," and if the prosecution had done that, they would be considered to have proved the words. This case refers to a decision of the Lahore High Court in Om Prakash v. Emperor, AIR 1930 Lah 867 wherein the contention was raised that the notes of a speech taken by a police officer were not admissible in evidence as he did not testify orally as to the speech and had not refreshed his memory under Section 159 of the Evidence Act from those notes. It was held that instead of deposing orally as to the speech made by the appellant, the police officer had put in the notes made by him, and that there would be no difference between this procedure and the police officer deposing orally after reference to those notes, and that for all practical purposes, that would be one and the same thing.20. The same view appears to us to have been taken in Emperor v. Balaram Das, AIR 1922 Cal 382 (2).21. From the discussion that we have made, we think that the correct legal position is somewhat like this.Normally, a police officer (or a Motbir) should reproduce the contents, of the statement made by the accused under Section 27 of the Evidence Act in Court by refreshing his memory under Section 159 of the Evidence Act from the memo earlier prepared thereof by him at the time the statement had been made to him or in his presence and which was recorded at the same time or soon after the making of it and that would be a perfectly unexceptionable way of proving such a statement. We do not think in this connection, however, that it would be correct to say that he can refer to the memo under Section 159 of the Evidence Act only if he establishes a case of lack of recollection and not otherwise. We further think that where the police officer swears that he does not remember the exact words used by the accused from lapse of time or a like cause or even where he does not positively say so but it is reasonably established from the surrounding circumstances (chief of which would be the intervening time between the making of the statement and the recording of the witness's deposition at the trial) that it could hardly be expected in the natural course of human conduct that he could or would have a precise or dependable recollection of the same, then under Section 160 of the Evidence Act, it would be open to the witness to rely on the document itself and swear that the contents thereof are correct where he is sure that they are so and such a case would naturally arise where he happens to have recorded the statement himself or where it has been recorded by some one else but in his own presence, and in such a case the document itself would be acceptable substantive evidence of the facts contained therein. With respect, we should further make it clear that in so far as Chhangani, J.'s holds to the contrary, we are unable to accept it as laying down the correct law. We hold accordingly."

Rejection of a bail application by Sessions Court does not operate as a bar for the High Court in entertaining a similar application under Section 439 Cr. P. C.

In the instant case, learned Principal Sessions Judge, Samba, has rejected the bail petition of both the petitioners. The question that arises for consideration is whether or not successive bail applications will lie before this Court. The law on this issue is very clear that

"It is significant to note that under Section 397, Cr.P.C of the new Code while the High Court and the Sessions Judge have the concurrent powers of revision, it is expressly provided under sub-section (3) of that section that when an application under that section has been made by any person to the High Court or to the Sessions Judge, no further application by the same person shall be entertained by the other of them. This is the position explicitly made clear under the new Code with regard to revision when the authorities have concurrent powers. Similar was the position under Section 435(4), Cr.P.C of the old Code with regard to concurrent revision powers of the Sessions Judge and the District Magistrate. Although, under Section 435(1) Cr.P.C of the old Code the High Court, a Sessions Judge or a District Magistrate had concurrent powers of revision, the High Court's jurisdiction in revision was left untouched. There is no provision in the new Code excluding the jurisdiction of the High Court in dealing with an application under Section 439(2), Cr.P.C to cancel bail after the Sessions Judge had been moved and an order had been passed by him granting bail. The High Court has undoubtedly jurisdiction to entertain the application under Section 439(2), Cr.P.C for cancellation of bail notwithstanding that the Sessions Judge had earlier admitted the appellants to bail. There is, therefore, no force in the submission of Mr Mukherjee to the contrary."[Para No.5]

"The above view of the learned Single Judge of the Kerala High Court appears to me to be correct. In fact, it is now well-settled that

there is no bar whatsoever for a party to approach either the High Court or the Sessions Court with an application for an ordinary bail made under Section 439 Cr.P.C. The power given by Section 439 to the High Court or to the Sessions Court is an independent power and thus, when the High Court acts in the exercise of such power it does not exercise any revisional jurisdiction, but its original special jurisdiction to grant bail. This being so, it becomes obvious that although under section 439 Cr.P.C. concurrent jurisdiction is given to the High Court and Sessions Court,the fact, that the Sessions Court has refused a bail under Section 439 does not operate as a bar for the High Court entertaining a similar application under Section 439 on the same facts and for the same offence. However,if the choice was made by the party to move first the High Court and the High Court has dismissed the application, then the decorum and the hierarchy of the Courts require that if the Sessions Court is moved with a similar application on the same fact, the said application be dismissed. This can be inferred also from the decision of the Supreme Court in Gurcharan Singh's case (above)."[Para No.6]

10 October 2020

Mere registration of FIR regarding ragging of a student is not the ground for suspending the accused-student from educational institute

Before suspending accused-student, the educational institute must get satisfied itself about the truth of allegations of ragging

09 October 2020

Court of Sessions can permit u/s. 301, 24(8) of CrPC to the advocate of victim to make oral argument too apart from submission of the written argument

Advocate is treated to be officer of the court and supposed to assist the court in arriving the truth, so, right to address the court to an Advocate cannot be curtailed while representing his client

04 October 2020

It amounts defamation u/s.499 of IPC if defamatory contents of pleading filed in a matrimonial case are revealed to relatives and friends of complainant

In the case of M.K. Prabhakaran and another Vs.T.E. Gangadharan and another reported in 2006 CRI.L.J. 1872, the Kerala High Court, in a matter where it is alleged that defamatory statements against complainant were made in a written statement filed before the Court held that,

"11. In Sandyal V.Bhaba Sundari Debi 7 Ind.Cas.803:15 C.W.N. 995:14 C.L.J.31 the learned Judges, following the case of Augada Ram Shaha V. Nemai Chand Shaha 23 C.867;12 Ind.Dec.(n.s.)576, held thatdefamatory statements made in the written statement of a party in a judicial proceedings are not absolutely privileged in this country, and that a qualified privilege in this regard cannot be claimed in respect of such statements, unless they fall within the Exceptions to Section 499 of the Indian Penal Code. Undisputedly, the case of the petitioner was not in any of these Exceptions.12. For criminal purposes "publication" has a wider meaning than it has in civil law, since it includes a communication to the person defamed alone.The prosecution for defamation in criminal cases can be brought although the only publication is to the person defamed as it is very likely to provoke a breach between the persons involved...."

02 October 2020

Husband is duty bound to maintain his dependants, regardless of his job and income

“4.Now that the matter is going back to the original Court we think it appropriate to bring it to the notice of the learned Magistrate that under Section 125 of the CrPCeven an illegitimate minor child is entitled to maintenance.

“The other findings of the Magistrate on the disputed question of fact were recorded after a full consideration of the evidence an should have been left undisturbed in revision. No error of law appears to have been discovered in his judgment and so the revisional courts were not justified in making a reassessment of the evidence and substitute their own views for those of the Magistrate. (See Pathumma and another v. Mahammad, [1986] 2 SCC 585). Besides holding that the respondent had married the appellant, the Magistrate categorically said that the appellant and the respondent lived together as husband and wife for a number of years and the appellant No. 2 Maroti was their child. If, as a matter of fact, a marriage although ineffective in the eye of law, took place between the appellant No. 1 and the respondent No. 1, the status of the boy must be held to be of a legitimate son on account of s. 16(1) of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, which reads as follows:

"16(1). Notwithstanding that a marriage is null and void under Section 11, any child of such marriage who would have been legitimate if the marriage had been valid, shall be legitimate, whether such child is born before or after the commencement of the Marriage Laws (Amendment) Act, 1976 (68 of 1976), and whether or not a decree of nullity is granted in respect of that marriage under this Act and whether or not the marriage is held to be void otherwise than on a petition under this Act."

01 October 2020

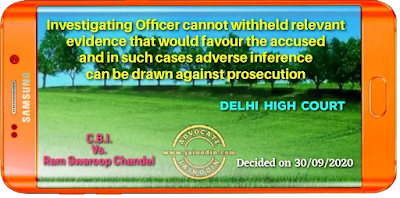

Investigating Officer cannot withheld relevant evidence that would favour the accused and in such cases adverse inference can be drawn against prosecution

If it appears impossible to convict accused inspite of witnesses are presumed to be true without any cross examination, the accused deserves to be discharge

"........8. The Court also noticed that seizure of large number of documents in the course of investigation of a criminal case is a common feature. After completion of the process of investigation and before submission of the report to the Court under Section 173 Cr.P.C, a fair amount of application of mind on the part of the investigating agency is inbuilt in the process. These documents would fall in two categories: one, which supports the prosecution case and other which supports the accused. At this stage, duty is cast on the investigating officer to evaluate the two sets of documents and materials collected and, if required, to exonerate the accused at that stage itself. However, many times it so happens that the investigating officer ignores the part of seized documents which favour the accused and forwards to the Court only those documents which supports the prosecution. If such a situation is pointed out by the accused and those documents which were supporting the accused and have not been forwarded and are not on the record of the Court, whether the prosecution would have to supply those documents when the accused person demands them? The Court did not answer this question specifically stating that the said question did not arise in the said case. In that case, the documents were forwarded to the Court under Section 173(5) Cr.P.C. but were not relied upon by the prosecution and the accused wanted copies/inspection of those documents. This Court held thatit was incumbent upon the trial court to supply the copies of these documents to the accused as that entitlement was a facet of just, fair and transparent investigation/trial and constituted an inalienable attribute of the process of a fair trial which Article 21 of the Constitution guarantees to every accused. We would like to reproduce the following portion of the said judgment discussing this aspect:"21.The issue that has emerged before us is, therefore, somewhat larger than what has been projected by the State and what has been dealt with by the High Court. The question arising would no longer be one of compliance or non- compliance with the provisions of Section 207 Cr.P.C. and would travel beyond the confines of the strict language of the provisions of Cr.P.C. and touch upon the larger doctrine of a free and fair trial that has been painstakingly built up by the courts on a purposive interpretation of Article 21 of the Constitution. It is not the stage of making of the request; the efflux of time that has occurred or the prior conduct of the accused that is material. What is of significance is if in a given situation the accused comes to the court contending that some papers forwarded to the court by the investigating agency have not been exhibited by the prosecution as the same favours the accused the court must concede a right to the accused to have an access to the said documents, if so claimed. This, according to us, is the core issue in the case which must be answered affirmatively. In this regard, we would like to be specific in saying that we find it difficult to agree with the view taken by the High Court that the accused must be made to await the conclusion of the trial to test the plea of prejudice that he may have raised. Such a plea must be answered at the earliest and certainly before the conclusion of the trial, even though it may be raised by the accused belatedly. This is how the scales of justice in our criminal jurisprudence have to be balanced."[Para No.63]

30 September 2020

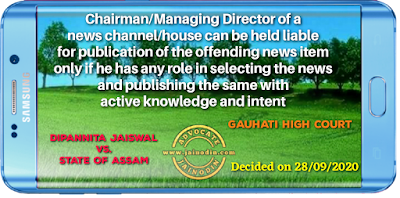

Chairman/Managing Director of a news channel/house can be held liable for publication of the offending news item only if he has any role in selecting the news and publishing the same with active knowledge and intent

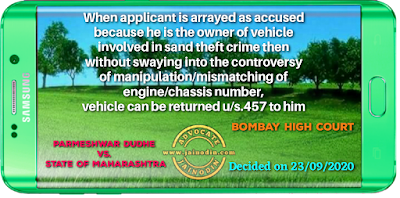

When applicant is arrayed as accused because he is the owner of vehicle involved in sand theft crime then without swaying into the controversy of manipulation/mismatching of engine/chassis number, vehicle can be returned u/s.457 to him

However as can be discerned, the matter has become complicated because of changes in the chassis and engine numbers appearing on the tractor. The panchnama under which the tractor was seized mentions that at the time of such seizure the chassis number was appearing as "0065110367V1DH" and the engine number was appearing as "CO6014709VIDK013B". Apparently no photograph of such number as they were appearing on the chassis and engine were taken. The petitioner had applied for release of the tractor earlier to the present attempt by filing Criminal M.A. No.569/2017 but it was rejected since the numbers obviously did not tally. He preferred Criminal Revision No.220/2017. It was dismissed but a direction was given to the RTO to inspect and to register the vehicle. Pursuant to such a direction the Magistrate called upon the RTO concerned to undertake the inspection and to register the tractor since it was not registered till then with the RTO. It is apparent that the RTO thereafter undertook the inspection on 26.12.2018 (page 40) and submitted a report on the same date to the Superintendent of the Civil Court at Sillod. In addition he sent another letter dated 08.01.2019 (page 43). It was mentioned that the tractor was having chassis number and engine number which tally with the original numbers mentioned by the dealer on the Tax Invoice (Exhibit B). However, he also notice that the tractor was not in a road worthy condition and therefore for the reasons mentioned therein he was unable to register it because of various provisions contained in the Motor Vehicles Act and the Rules framed thereunder. It is in the backdrop of such state of affairs that now we are faced with the situation.[Para No.13]

29 September 2020

Accused can be released on interim bail on the ground of snail speed of the trial

Successive application for bail is permissible under substantial change of circumstances which has direct impact on the earlier decision and not merely cosmetic changes

"19.....However, unintentional and unavoidable delays or administrative factors over which prosecution has no control, such as, over- crowded court dockets, absence of the presiding officers, strike by the lawyers, delay by the superior forum in notifying the designated Judge, (in the present case only), the matter pending before the other forums, including High Courts and Supreme Courts and adjournment of the criminal trial at the instance of the accused, may be a good cause for the failure to complete the trial within a reasonable time. This is only illustrative and not exhaustive. Such delay or delays cannot be violative of accused's right to a speedy trial and needs to be excluded while deciding whether there is unreasonable and unexplained delay..."

28 September 2020

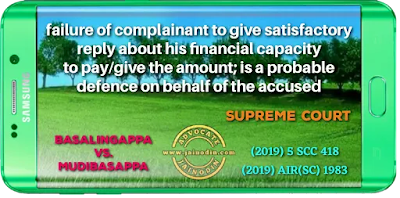

In cheque dishonor case; failure of complainant to give satisfactory reply about his financial capacity to pay/give the amount; is a probable defence on behalf of the accused

25 September 2020

While deciding bail application, it cannot be presumed that petitioner will flee justice or will influence the investigation/witnesses

Grant of bail cannot be thwarted merely by asserting that offence is grave.

Consequences of pre-trial detention are grave.

In AIR 2019 SC 5272, titled P. Chidambaram v. Central Bureau of Investigation, CBI had opposed the bail plea on the grounds of:- (i) flight risk; (ii) tampering with evidence; and (iii) influencing witnesses. The first two contentions were rejected by the High Court. But bail was declined on the ground that possibility of influencing the witnesses in the ongoing investigation cannot be ruled out. Hon'ble Apex Court after considering (2001) 4 SCC 280, titled Prahlad Singh Bhati v. NCT, Delhi and another;( 2004) 7 SCC 528, titled Kalyan Chandra sarkar v.R ajesh Ranjan and another; (2005) 2 SCC 13, titled Jayendra Saraswathi Swamigal v. State of Tamil Nadu and (2005) 8 SCC 21, titled State of U.P. through CBI v.Amarmani Tripathi, observed as under:-

"26. As discussed earlier, insofar as the "flight risk" and "tampering with evidence" are concerned, the High Court held in favour of the appellant by holding that the appellant is not a "flight risk" i.e. "no possibility of his abscondence". The High Court rightly held that by issuing certain directions like "surrender of passport", "issuance of look out notice", "flight risk" can be secured. So far as "tampering with evidence" is concerned, the High Court rightly held that the documents relating to the case are in the custody of the prosecuting agency, Government of India and the Court and there is no chance of the appellant tampering with evidence.

28. So far as the allegation of possibility of influencing the witnesses, the High Court referred to the arguments of the learned Solicitor General which is said to have been a part of a "sealed cover" that two material witnesses are alleged to have been approached not to disclose any information regarding the appellant and his son and the High Court observed that the possibility of influencing the witnesses by the appellant cannot be ruled out. The relevant portion of the impugned judgment of the High Court in para (72) reads as under:

"72. As argued by learned Solicitor General, (which is part of 'Sealed Cover', two material witnesses (accused) have been approached for not to disclose any information regarding the petitioner and his son (co-accused). This court cannot dispute the fact that petitioner has been a strong Finance Minister and Home Minister and presently, Member of Indian Parliament. He is respectable member of the Bar Association of Supreme Court of India. He has long standing in BAR as a Senior Advocate. He has deep root in the Indian Society and may be some connection in abroad. But, the fact that he will not influence the witnesses directly or indirectly, cannot be ruled out in view of above facts. Moreover, the investigation is at advance stage, therefore, this Court is not inclined to grant bail."

29. FIR was registered by the CBI on 15.05.2017. The appellant was granted interim protection on 31.05.2018 till 20.08.2019. Till the date, there has been no allegation regarding influencing of any witness by the appellant or his men directly or indirectly. In the number of remand applications, there was no whisper that any material witness has been approached not to disclose information about the appellant and his son. It appears that only at the time of opposing the bail and in the counter affidavit filed by the CBI before the High Court, the averments were made that "....the appellant is trying to influence the witnesses and if enlarged on bail, would further pressurize the witnesses....". CBI has no direct evidence against the appellant regarding the allegation of appellant directly or indirectly influencing the witnesses. As rightly contended by the learned Senior counsel for the appellant, no material particulars were produced before the High Court as to when and how those two material witnesses were approached. There are no details as to the form of approach of those two witnesses either SMS, email, letter or telephonic calls and the persons who have approached the material witnesses. Details are also not available as to when, where and how those witnesses were approached.

31. It is to be pointed out that the respondent - CBI has filed remand applications seeking remand of the appellant on various dates viz. 22.08.2019, 26.08.2019, 30.08.2019, 02.09.2019, 05.09.2019 and 19.09.2019 etc. In these applications, there were no allegations that the appellant was trying to influence the witnesses and that any material witnesses (accused) have been approached not to disclose information about the appellant and his son. In the absence of any contemporaneous materials, no weight could be attached to the allegation that the appellant has been influencing the witnesses by approaching the witnesses. The conclusion of the learned Single Judge "...that it cannot be ruled out that the petitioner will not influence the witnesses directly or indirectly....." is not substantiated by any materials and is only a generalised apprehension and appears to be speculative. Mere averments that the appellant approached the witnesses and the assertion that the appellant would further pressurize the witnesses, without any material basis cannot be the reason to deny regular bail to the appellant; more so, when the appellant has been in custody for nearly two months, co-operated with the investigating agency and the charge sheet is also filed.

32. The appellant is not a "flight risk" and in view of the conditions imposed, there is no possibility of his abscondence from the trial. Statement of the prosecution that the appellant has influenced the witnesses and there is likelihood of his further influencing the witnesses cannot be the ground to deny bail to the appellant particularly, when there is no such whisper in the six remand applications filed by the prosecution. The charge sheet has been filed against the appellant and other co-accused on 18.10.2019. The appellant is in custody from 21.08.2019 for about two months. The co-accused were already granted bail. The appellant is said to be aged 74 years and is also said to be suffering from age related health problems. Considering the above factors and the facts and circumstances of the case, we are of the view that the appellant is entitled to be granted bail."[Para No.5.v.6]

16 September 2020

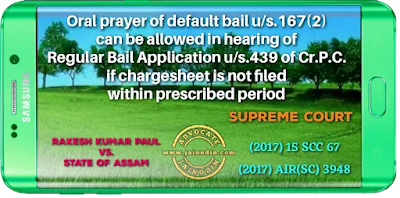

Oral prayer of default bail u/s.167(2) can be allowed in hearing of Regular Bail Application u/s.439 of Cr.P.C. if chargesheet is not filed within prescribed period

15 September 2020

Bail cannot be withheld merely as a punishment

When accused surrendered before Sessions court, the court has powers u/s.439 of Cr.P.C. to release accused on personal bond for a short period pending the disposal of a bail application

12 September 2020

Neither District Administration nor Police have any powers to seize immovable property for violation of lockdown orders

"20. Section 102 postulates seizure of the property. Immovable property cannot, in its strict sense, be seized, though documents of title, etc. relating to immovable property can be seized, taken into custody and produced. Immovable property can be attached and also locked/sealed. It could be argued that the word 'seize' would include such action of attachment and sealing. Seizure of immovable property in this sense and manner would in law require dispossession of the person in occupation/possession of the immovable property, unless there are no claimants, which would be rare. Language of Section 102 of the Code does not support the interpretation that the police officer has the power to dispossess a person in occupation and take possession of an immovable property in order to seize it. In the absence of the Legislature conferring this express or implied power under Section 102 of the Code to the police officer, we would hesitate and not hold that this power should be inferred and is implicit in the power to effect seizure. Equally important, for the purpose of interpretation is the scope and object of Section 102 of the Code, which is to help and assist investigation and to enable the police officer to collect and collate evidence to be produced to prove the charge complained of and set up in the charge sheet. The Section is a part of the provisions concerning investigation undertaken by the police officer. After the charge sheet is filed, the prosecution leads and produces evidence to secure conviction.Section 102 is not, per se, an enabling provision by which the police officer acts to seize the property to do justice and to hand over the property to a person whom the police officer feels is the rightful and true owner. This is clear from the objective behind Section 102, use of the words in the Section and the scope and ambit of the power conferred on the Criminal Court vide Sections 451 to 459 of the Code. The expression 'circumstances which create suspicion of the commission of any offence' in Section 102 does not refer to a firm opinion or an adjudication/finding by a police officer to ascertain whether or not 'any property' is required to be seized. The word 'suspicion' is a weaker and a broader expression than 'reasonable belief' or 'satisfaction'.The police officer is an investigator and not an adjudicator or a decision maker. This is the reason why the Ordinance was enacted to deal with attachment of money and immovable properties in cases of scheduled offences. In case and if we allow the police officer to 'seize' immovable property on a mere 'suspicion of the commission of any offence', it would mean and imply giving a drastic and extreme power to dispossess etc. to the police officer on a mere conjecture and surmise, that is, on suspicion, which has hitherto not been exercised. We have hardly come across any case where immovable property was seized vide an attachment order that was treated as a seizure order by police officer under Section 102 of the Code. The reason is obvious. Disputes relating to title, possession, etc., of immovable property are civil disputes which have to be decided and adjudicated in Civil Courts. We must discourage and stall any attempt to convert civil disputes into criminal cases to put pressure on the other side (See Binod Kumar v. State of Bihar (2014)10SCC663).Thus, it will not be proper to hold that Section 102 of the Code empowers a police officer to seize immovable property, land, plots, residential houses, streets or similar properties. Given the nature of criminal litigation, such seizure of an immovable property by the police officer in the form of an attachment and dispossession would not facilitate investigation to collect evidence/material to be produced during inquiry and trial. As far as possession of the immovable property is concerned, specific provisions in the form of Sections 145 and 146 of the Code can be invoked as per and in accordance with law.Section 102 of the Code is not a general provision which enables and authorises the police officer to seize immovable property for being able to be produced in the Criminal Court during trial. This, however, would not bar or prohibit the police officer from seizing documents/papers of title relating to immovable property, as it is distinct and different from seizure of immovable property. Disputes and matters relating to the physical and legal possession and title of the property must be adjudicated upon by a Civil Court.

21. In view of the aforesaid discussion, the Reference is answered by holding thatthe power of a police officer under Section 102 of the Code to seize any property, which may be found under circumstances that create suspicion of the commission of any offence, would not include the power to attach, seize and seal an immovable property." [Para No.12]