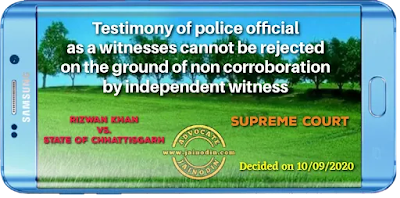

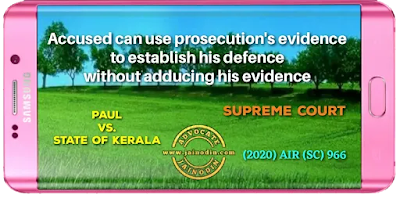

Having gone through the entire evidence on record and the findings recorded by the courts below, we are of the opinion that in the present case the prosecution has been successful in proving the case against the accused by examining the witnesses PW3, PW4, PW5, PW7 and PW8. It is true that all the aforesaid witnesses are police officials and two independent witnesses who were panchnama witnesses had turned hostile. However, all the aforesaid police witnesses are found to be reliable and trustworthy. All of them have been thoroughly crossexamined by the defence. There is no allegation of any enmity between the police witnesses and the accused. No such defence has been taken in the statement under Section 313, Cr.P.C. There is no law that the evidence of police officials, unless supported by independent evidence, is to be discarded and/or unworthy of acceptance.

It is settled law that the testimony of the official witnesses cannot be rejected on the ground of noncorroboration by independent witness. As observed and held by this Court in catena of decisions, examination of independent witnesses is not an indispensable requirement and such nonexamination is not necessarily fatal to the prosecution case, [see Pardeep Kumar (supra)].

In the recent decision in the case of Surinder Kumar v. State of Punjab, (2020) 2 SCC 563, while considering somewhat similar submission of nonexamination of independent witnesses, while dealing with the offence under the NDPS Act, in paragraphs 15 and 16, this Court observed and held as under:

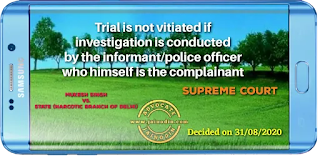

“15. The judgment in Jarnail Singh v. State of Punjab (2011) 3 SCC 521, relied on by the counsel for the respondent State also supports the case of the prosecution. In the aforesaid judgment, this Court has held thatmerely because prosecution did not examine any independent witness, would not necessarily lead to conclusion that the accused was falsely implicated. The evidence of official witnesses cannot be distrusted and disbelieved, merely on account of their official status.

16. In State (NCT of Delhi) v. Sunil, (2011) 1 SCC 652, it was held as under: (SCC p. 655) “It is an archaic notion that actions of the police officer should be approached with initial distrust. It is time now to start placing at least initial trust on the actions and the documents made by the police. At any rate, the court cannot start with the presumption that the police records are untrustworthy.

As a proposition of law, the presumption should be the other way round. That official acts of the police have been regularly performed is a wise principle of presumption and recognised even by the legislature.”